Cynocephali

This creature that we will be exploring is an ancient one. As it turns out, historians have recorded their existence for a long, long, time.

An old book rests comfortably on a shelf in the Vatican library, after coming to peace with the notion that no one will believe him any longer. A group of maps from long ago sigh heavily as their dust eats away at their fading colors in the closet of a large museum. A stone wall, cut from an ancient palace, lays naked before its curators and historians as they decide the difference between what it depicts and what they believe to be possible. The conclusion is obvious.

"It must be a metaphor."

Among the many documents, maps, art, and architecture, people have found evidence of a creature that seems utterly unbelievable.

They call them Cynocephali: the dog-headed people.

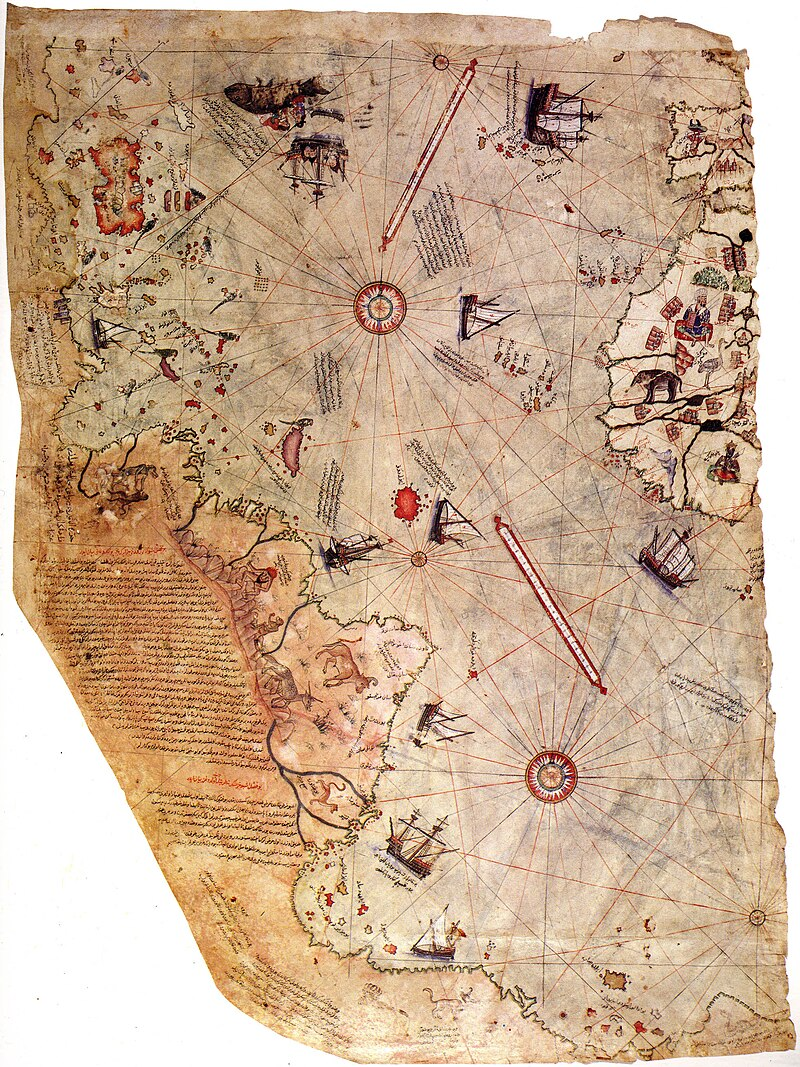

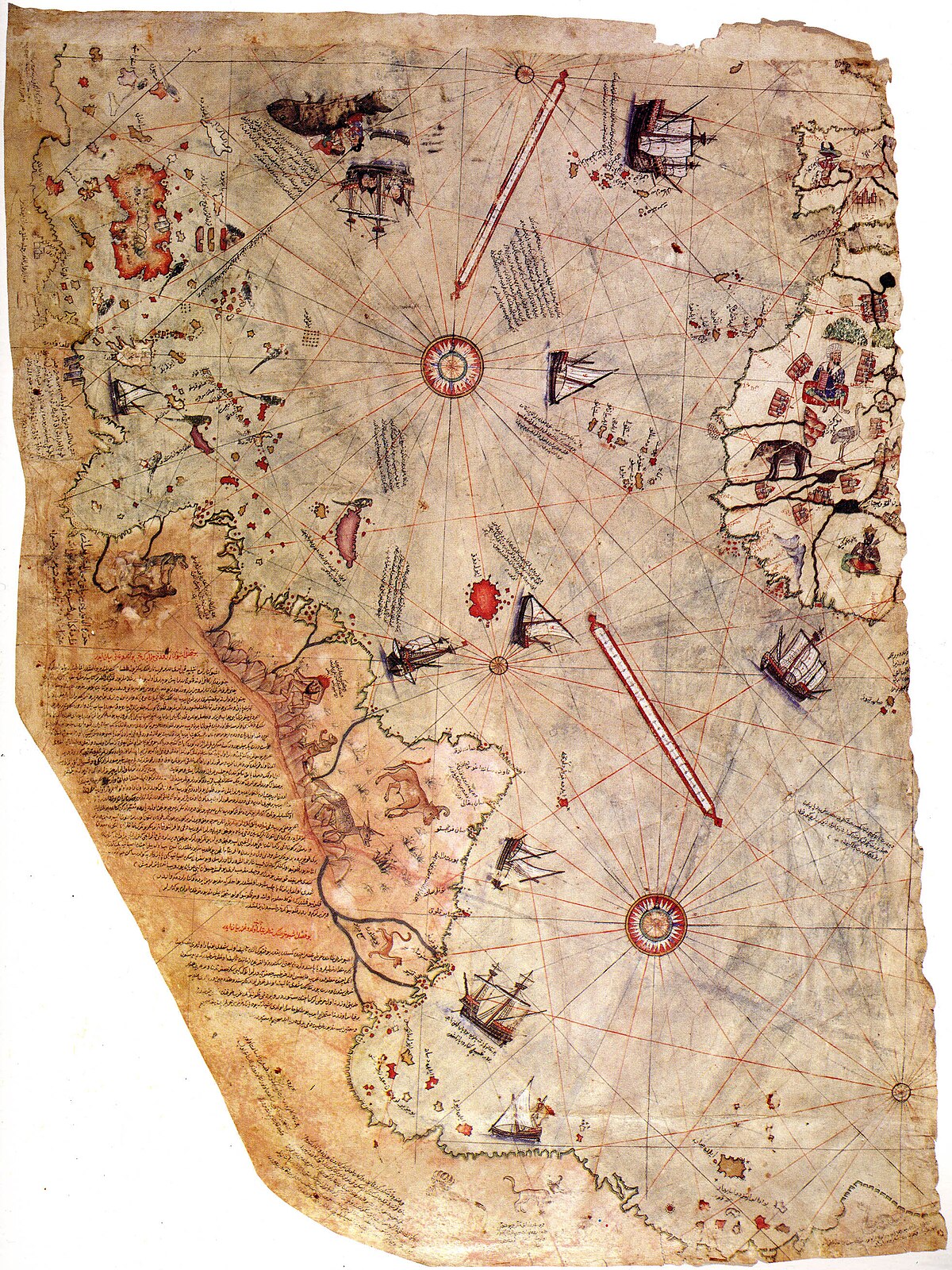

I encountered this concept on a summer afternoon while examining ancient maps I had somewhat recently purchased. One of the maps, from the Ottoman Empire, depicted a strange creature in South America. The creature seemed oddly similar to a human but its head was that of a different creature entirely. The map was called the Piri Reis map. It was presented to Sultan Selim I in 1517 and was used by sailors and explorers of his empire. Little did I know that this was only the first of many maps I would find with the same or similar creatures. I grew increasingly curious and found myself studying a concept I would have previously laughed at had anyone proposed it. Over a very short time period, I found myself with more evidence than I could handle and it quickly overwhelmed me. What follows is an attempt to cover the mere basics and present only a reasonable sample of what I found.

This creature that we will be exploring is an ancient one. As it turns out, historians have recorded their existence for a long, long, time.

Historians and Explorers

Historians are the gatekeepers of the past. They devote their lives to that which was, in pursuit of that which will always remain; the truth. Ancient historians have long written of the cynocephali, whether by the witness of their own eyes or second-hand accounts (historians call them Primary and Secondary sources respectively). Flipping through the pages of time, one can find dozens of credible historians, upon which much of our modern understanding of the past relies. These very men speak of these creatures in their writings as a real race of men.

5th century BC: Herodotus

The earliest writings we have about the Cynocephali are by the world-renowned Herodotus, known as the father of history, from the 5th century BC. In my research on the topic of the cynocephali, I found this quote by him from his historical works.

Herodotus, Book 4: "...for in the land of these are found both the monstrous serpent and the lion and the elephant, and the bears and the venomous snakes and horned asses, besides the dog-headed men..."

Herodotus includes the dog-headed men as if it were a well-understood topic. He assumes the reader must already know of them just as they must know what a serpent, lion, and elephant are. Interestingly, even though he mentions this race of dog-headed men in Libya he also states in the same book that he doesn't believe in werewolves.

Histories, Book 4: "These men it would seem are wizards; for it is said of them by the Scythians and by the Hellenes who are settled in the Scythian land that once in every year each of the Neuroi becomes a wolf for a few days and then returns again to his original form. For my part I do not believe them when they say this, but they say it nevertheless, and swear it moreover."

Anyone who has read Histories by Herodotus knows that he points out when he doesn't believe something and in this case, it is wizards who turn into werewolves. The fact that he mentions a race of dog-headed men and assumes your knowledge of them yet speaks out against the folklore of werewolves is fascinating to anyone paying attention. To any civilian of the modern day, believing in a race of dog-headed men is just as crazy as werewolves, but for whatever reason Herodotus seems to disagree.

With more questions than answers from Herodotus, the next few writings await circa 1 century later.

4th century BC: Ctesias, Megasthenes, Alexander the Great

Ctesias was a Greek physician and historian who lived in the 5th century BC. He is best known for his works on Persia and India, which were based on his own experiences as a physician at the court of the Persian king Artaxerxes II. In one of his works, he wrote about cynocephali in India with quite a bit of detail.

Ctesias: "On these [the Indian] mountains there live men with the head of a dog, whose clothing is the skin of wild beasts. They speak no language, but bark like dogs, and in this manner make themselves understood by each other. Their teeth are larger than those of dogs, their nails like those of these animals, but longer and rounder. They inhabit the mountains as far as the river Indos. Their complexion is swarthy. They are extremely just, like the rest of the Indians with whom they associate. They understand the Indian language but are unable to converse, only barking or making signs with their hands and fingers by way of reply, like the deaf and dumb. They are called by the Indians Kalystrii, in Greek Kynocephaloi (Cynocephali) (Dog-Headed). They live on raw meat and number about 120,000 . . .

The Kynokephaloi living on the mountains do not practise any trade but live by hunting. When they have killed an animal they roast it in the sun. They also rear numbers of sheep, goats, and asses, drinking the milk of the sheep and whey made from it. They eat the fruit of the Siptakhora (Siptachora), whence amber is procured, since it is sweet. They also dry it and keep it in baskets, as the Greeks keep their dried grapes. They make rafts which they load with this fruit together with well-cleaned purple flowers and 260 talents of amber, with the same quantity of the purple dye, and 1000 additional talents of amber, which they send annually to the king of India. They exchange the rest for bread, flour, and cotton stuffs with the Indians, from whom they also buy swords for hunting wild beasts, bows, and arrows, being very skilful in drawing the bow and hurling the spear. They cannot be defeated in war, since they inhabit lofty and inaccessible mountains. Every five years the king sends them a present of 300,000 bows, as many spears, 120,000 shields, and 50,000 swords.

They do not live in houses, but in caves. They set out for the chase with bows and spears, and as they are very swift of foot, they pursue and soon overtake their quarry. The women have a bath once a month, the men do not have a bath at all, but only wash their hands. They anoint themselves three times a month with oil made from milk and wipe themselves with skins. The clothes of men and women alike are not skins with the hair on, but skins tanned and very fine. The richest wear linen clothes, but they are few in number. They have no beds, but sleep on leaves or grass. He who possesses the greatest number of sheep is considered the richest, and so in regard to their other possessions. All, both men and women, have tails above their hips, like dogs, but longer and more hairy. They are just, and live longer than any other men, 170, sometimes 200 years."

Ctesias goes into detail on this strange race of men. He speaks of their communication methods, engineering, commodities, trading preferences, weapons of choice, housing, self-care, clothing, forms of wealth, and lifespan.

His writings are both praised and ridiculed in modern scholarly work, but for roughly a thousand years his works were highly regarded. Still, there are more controversial works than his from this century.

Sometime after the conquests that Ctesias accompanied his king for, Alexander the Great tore his way through armies and conquered much of the known world. To quote Sam Ottewill-Soulsby from the University of Cambridge:

"Developing out of the Greek Pseudo-Callisthenes tradition, the Letter of Alexander to Aristotle was highly popular in the medieval Latin west. While the first Latin manuscript dates to the ninth century, quotations elsewhere indicate that it had been translated from Greek by the seventh century. In the letter, Alexander recounts his adventures in India to his tutor, including an encounter with the cynocephali:"

The quote he provides is as follows:

Alexander the Great: "Next we found a grove full of huge cynocephali who tried to harass us but they began to flee when we shot our arrows. Now as we were entering a deserted area, the Indians reported that there was nothing more worth seeing"

Although the letter was held in high regard by historians for hundreds of years, it has since come under scrutiny and its authenticity has become a debated topic. This being said, even if the letter wasn't truly written by the Great Alexander himself, it remains a document providing evidence for the belief in such creatures as the cynocephali. Held under considerably less scrutiny, however, Megasthenes was yet another author from this century who wrote on the subject.

Megasthenes was a Greek historian, diplomat, and ethnographer who lived in the 4th century BC. He is best known for his work Indica, which is a description of India based on his own experiences as a diplomat at the court of Chandragupta Maurya, the first emperor of the Maurya Empire. In his writings, he describes the cynocephali race as a friend to the Indian nation.

Megasthenes: "on different mountains in India there are tribes of men with dog-shaped heads, armed with claws, clothed with skins, who speak not in the accents of human language, but only bark, and have fierce grinning jaws."

Megasthenes' writings would go on to be referenced by many scholars for more than a thousand years, even today, and even his mention of the cynocephali was quoted and or referenced by medical scholars such as Pliny the Elder.

These accounts of cynocephali living in India are intriguing, to say the least, but India is not the only location we hear of in the 4th century BC. Berosus writes of them being in Babylonia, according to others he had spoken to.

3rd century BC: Berosus, Manetho

Berosus: "In the land of Babylonia, there is a race of men who have the heads of dogs and the bodies of men. They are said to be very wise and to be able to predict the future."

Berosus was a Babylonian priest and astronomer who lived in the 3rd century BC. He is best known for his work Babyloniaca, which is a history of Babylonia from the creation of the world to his own time.

Manetho was an Egyptian priest of the god Hephaestus from Sebennytos in the Delta of Egypt, who lived during the Ptolemaic Kingdom in the early 3rd century BC. He is best known for his Aegyptiaca, a history of Egypt in Greek, which is the only surviving comprehensive ancient Egyptian history from the Ptolemaic period. In that very writing he spoke of the cynocephali as living in the land of Punt in Africa.

Manetho: "In the land of Punt, which is located in Africa, there is a race of men who have the heads of dogs and the bodies of men. They are said to be very intelligent and to be able to speak the language of the Puntites."

Manetho's Aegyptiaca was a popular work in the ancient world. It was translated into Latin and Syriac, and it was used by later historians, such as Josephus and Eusebius. Some scholars claim inaccuracies in his writing, and Aegyptiaca along with the rest of these sources aren't full-proof arguments on their own, but collectively they continue to paint a picture that begs to be interpreted.

1st century BC-AD: Pliny the Elder, Pomponius Mela, Strabo

In the first century BC and AD I found a collection of writings from 3 different authors that mention the creature in question.

Pliny the Elder (Gaius Plinius Secundus; 23–79 AD) was a Roman author, naturalist, and natural philosopher. He is best known for his work Naturalis Historia, an encyclopedia of natural history that is one of the most comprehensive works of its kind from the ancient world.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History 7.2:40-41: "On many of the mountains again, there is a tribe of men who have the heads of dogs, and clothe themselves with the skins of wild beasts. Instead of speaking, they bark; and, furnished with claws, they live by hunting and catching birds. According to the story, as given by Ctesias, the number of these people is more than a hundred and twenty thousand..."

Pliny affirms and references Ctesias, quoting his work on the mention of the hundred and twenty thousand. Pliny chooses to point out the clothing, communication method, and form of hunting much like Ctesias. It's interesting to recognize that he read what Ctesias said about the cynocephali but only said a fraction of the things that Ctesias did. This could be for various reasons, but ultimately we can't know why for sure.

Pliny writes about many fantastical so-called monstrous races, which many point to as a reason to doubt his writings, but Pliny wasn't the type to accept anything he heard.

Piny The Elder, Natural History 8.34:2-4: "That men have been turned into wolves, and again restored to their original form, we must confidently look upon as untrue, unless, indeed, we are ready to believe all the tales, which, for so many ages, have been found to be fabulous. But, as the belief of it has become so firmly fixed in the minds of the common people, as to have caused the term "Versipellis" to be used as a common form of imprecation, I will here point out its origin."

Pliny mentions, shortly after mentioning a race of dog-headed men, that belief in werewolves is foolishness. He seemed to believe there was evidence for one and none for the other. This echoes the perspective of Herodotus.

Pliny's mention of the cynocephali is somewhat brief compared to the ancient scholar he references but he isn't the only Roman scholar of his time to mention these creatures. Pomponius Mela writes of the cynocephali roughly around the same time.

Pomponius Mela was a Roman geographer who lived in the 1st century AD. He is best known for his work De Chorographia, which is a description of the known world in his time.

Pomponius Mela: "In the island of Cynocephalae, which lies off the coast of India, there is a race of men who have the heads of dogs and the bodies of men. They are said to be very friendly and to be good friends to the Indians."

Pomponius mentions the dog-headed race of men as living on an island off the coast of India. Rather than pointing out other details about these creatures in question, he chooses to focus on the fact that they are said to be very friendly people. There was a Greek historian who said something similar around the same time. Although it agrees with the writers previously mentioned, it spurs much disagreement between modern scholars. However, modern scholars are not the only ones arguing against authors who describe these creatures. A fascinating account is given by Strabo who spoke against the existence of the Cynocephali.

Strabo (c. 64 or 63 BC – c. 24 AD) was a Greek geographer and historian who lived in Asia Minor during the transitional period of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. He is best known for his work Geography, which is a detailed description of the known world in his time. In this work, he, although clearly ridiculing the belief in such creatures, provides one of the only written accounts stating that Hesiod wrote of a race of half-dog men.

Geography 7.3

"But this ignorance in Homer's case is not amazing, for those who have lived later than he have been ignorant of many things and have invented marvellous tales: Hesiod, when he speaks of “men who are half-dog,”44 of “long-headed men,” and of “Pygmies”; and Alcman, when he speaks of “web footed men”; and Aeschylus, when he speaks of “dog-headed men,” of “men with eyes in their breasts”, and of “one-eyed men” (in his Prometheus it is said45); and a host of other tales."

Hesiod was a Greek author and poet from the 8th century BC, making him the oldest author to (potentially) mention these creatures in Greek history. Though his writings containing such descriptions, along with much of his work, are long gone Strabo gives us reason to believe he did in fact write about them. Strabo writes of Hesiod's mention of these creatures looking down on it as foolishness, so it's highly unlikely that he's lying or even misinformed. The very nature of Strabo's polemic work is the strongest argument for the existence of such material by Hesiod known to date.

2nd century AD: Aelian, Solinus, Ptolemy

Aelian, or Claudius Aelianus, was a Roman author and teacher of rhetoric who lived in the 2nd century AD. He is best known for his work Varia Historia, a collection of anecdotes and stories about animals, plants, and people.

Aelian's On The Nature Of Animals, Book IV: "In the same part of India are found the creatures we call DOG-HEADS, a name that they earn because that is just how they look. They have human shape, but they are clothed in fur. They walk upright. They are no threat to humans. They howl instead of speaking, but they understand the language of the people there. They chase down wild animals very easily and cook them and eat them—cook them not with flame, but simply by tearing them apart and then letting the sun sear the meat. They keep goats and sheep for milk. I include them among the beasts, logically, since their language is unintelligible to humans."

Aelian's description should seem familiar by now. He points out their methods of communication, cooking, and preferred foods. Again, India is where he mentions them living. When he mentions "the same part of India" he is referring to a mountainous region. In the same century of Alian's writings, Gaius Julius Solinus spoke up on this strange topic.

Gaius Julius Solinus, better known simply as Solinus, was a Latin grammarian, geographer, and compiler who probably flourished in the early 3rd century AD. He is best known for his work De mirabilibus mundi ("The wonders of the world") which circulated both under the title Collectanea rerum memorabilium ("Collection of Curiosities"), and Polyhistor, though the latter title was favored by the author himself.

Solinus: "In the island of Cynocephalae, which lies off the coast of India, there are men who have the heads of dogs and the bodies of men. They are said to be very intelligent and to be able to speak the language of the Indians."

Solinus' work is a compilation of information from a variety of sources, including Pliny the Elder, Pomponius Mela, and Aelian. He also drew on his own knowledge of the ancient world, which he may have gained through travel or through reading. Given these facts, Solinus is certainly basing his statements on authors already previously mentioned but it is worthwhile in noting that he believed these statements enough to attach his name to them. The same seems to be true for Ptolemy, as he seems to be quoting historical works.

Claudius Ptolemy was a Greco-Egyptian astronomer, mathematician, geographer, and astrologer. He lived in Alexandria, Egypt, during the Roman Empire. He is best known for his work Almagest, which is a treatise on astronomy that was the standard text for teaching and discussing astronomy for centuries.

Ptolemy was born in Alexandria, Egypt, to a family of astronomers. He studied mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy at the Museum of Alexandria, which was a center of learning in the ancient world. He had a reputation to uphold, even more so than Solinus, yet he too attaches his name to the following statement.

Ptolemy: "In the interior of Ethiopia there is a race of men who have the heads of dogs and the bodies of men. They are said to be very savage and to live by hunting and eating raw flesh."

While these writings are far from first-hand accounts, they have credibility in and of themselves. These writings seem to shoot down the argument one might make about motive. These men were well-respected individuals, much like those who wrote the original statements, they had little to gain and much to lose in terms of reputation. Ptolemy was born and raised at the epicenter of ancient knowledge and academia, and even he ascribed to the notion of these creatures being a very real thing.

5th century AD: Saint Augustine

On the topic of monstrous races, including the Cyncephali, Augustine carefully rides the line neither fully affirming their existence nor denying it.

Augustine, City of God: "Wherefore, to conclude this question cautiously and guardedly, either these things which have been told of some races have no existence at all; or if they do exist, they are not human races; or if they are human, they are descended from Adam."

He, not knowing for sure, points out not everything should be taken simply at the word of many nor should it be outwardly denied on the grounds of unlikelihood.

Augustine, City of God: "It is also asked whether we are to believe that certain monstrous races of men, spoken of in secular history, have sprung from Noah’s sons, or rather, I should say, from that one man from whom they themselves were descended...What shall I say of the Cynocephali, whose dog-like head and barking proclaim them beasts rather than men? But we are not bound to believe all we hear of these monstrosities."

By the 5th century, it seems the existence of the cynocephali was in question by some and still professed by others. Augustine acknowledges it as a popular topic but remains neutral in terms of confirming or denying their existence.

7th century AD: Isidore of Seville

A few centuries later, Isidore of Seville joined this very old and global conversation.

Isidore of Seville, Etymologies XI.iii.12–iii.14

"Just as, in individual nations, there are instances of monstrous people, so in the whole of humankind there are certain monstrous races, like the Giants, the Cynocephali (i.e. ‘dog-headed people’), the Cyclopes, and others...The Cynocephali are so called because they have dogs’ heads, and their barking indeed reveals that they are rather beasts than humans. These originate in India."

Isidore of Seville (c. 560 – April 4, 636) was a Hispano-Roman scholar, theologian, and archbishop of Seville. He is widely regarded, in the words of 19th-century historian Montalembert, as "the last scholar of the ancient world". Isidore was also a skilled diplomat, and he helped to negotiate peace between the Visigoths and the Byzantine Empire. He was a wise and learned man, and he was respected by both Christians and Muslims.

Isidore's most famous work is The Etymologies, a vast encyclopedia of knowledge that is divided into 20 books. The Etymologies covers a wide range of topics, including grammar, rhetoric, philosophy, theology, and natural science. It was a popular work in the Middle Ages, and it was used by scholars and students for centuries.

12th century AD: Al-Idrisi

Abu Abdullah Muhammad al-Idrisi al-Qurtubi al-Hasani as-Sabti, also known simply as al-Idrisi, was a Muslim geographer and cartographer who served in the court of King Roger II at Palermo, Sicily. He was born in Ceuta, then belonging to the Almoravid dynasty. He created the Tabula Rogeriana, one of the most advanced medieval world maps. Al-Idrisi studied geography, astronomy, and mathematics. He also traveled widely, visiting many parts of the world, including Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Al-Idrisi also wrote a book about the map called the Kitab Nuzhat al-Mushtaq fi Ikhtiraq al-Afaq, which means "The Book of Pleasant Excursions to the Regions of the World". The book is a description of the world, and it includes information about the geography, history, and culture of different regions. In this book, he wrote of the cynocephali as being in China and actually being able to speak Chinese.

Al-Idrisi: "In the land of China, there is a race of men who have the heads of dogs and the bodies of men. They are said to be very intelligent and to be able to speak the language of the Chinese."

Al-Idrisi wasn't the only to claim the cynocephali were in Asia. A century later, Marco Polo actually made the claim that a fierce group of them living outside of Great Khan's territory.

13th century AD: Marco Polo, Vincent of Beauvais

Marco Polo, as you might know, was a Venetian merchant and explorer who traveled to Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in The Travels of Marco Polo, a book that describes for Europeans the wonders of China, its capital Peking (now Beijing), and other cities and countries of Asia.

Marco Polo: "In the land of Lofo-lan, which is near the Great Khan's dominions, there are men who have the heads of dogs and the bodies of men. They are said to be very fierce and to live by hunting."

Whether or not Marco Polo saw these creatures himself we do not know, but their existence was clearly still believed in China around his lifetime if he simply heard of them. Around this same time, the concept of them living off the coast of India sprouted up again but this time in the words of Vincent of Beauvais.

Vincent of Beauvais was a French Dominican friar and encyclopedist who lived from c. 1184/1194 to c. 1264. He is best known for his Speculum Maius, a massive encyclopedia that was one of the most important works of scholarship in the Middle Ages. Vincent of Beauvais was a prolific writer and a brilliant thinker. His work had a profound impact on the development of scholarship and education in the Middle Ages. He is considered one of the most important figures in the history of the Dominican order. The Speculum Naturale is the first part of Vincent of Beauvais's Speculum Maius, and in it, he speaks of the cynocephali as being off the coast of India (much like many previous historians).

Vincent of Beauvais: "There are also men with dog's heads. They are said to inhabit an island called Cynocephala, which is situated off the coast of India."

Vincent of Beauvais and his account of the cynocephali seem to fit the pattern, but a century later a book was released that most certainly did not.

14th century AD: John Mandeville

John Mandeville was the purported author of a travelogue titled The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, which was one of the most popular books of the Middle Ages. The book describes Mandeville's travels to Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.

Historians, however, argue there is no evidence that John Mandeville ever existed. Officially, the book is now believed to be a work of fiction, written by an anonymous author in the late 14th or early 15th century. This is understandable. The Travels of Sir John Mandeville is filled with descriptions of many wild beasts and creatures but as always we should be careful not to throw the baby out with the bath water. This book, however fantastical it may be, irrefutably contains perfectly accurate information alongside the fantastical. In fact, this work was even used and referenced by Christopher Columbus. It describes well-known nations and peoples, their beliefs, their languages, and their alphabets. It's also written from a catholic perspective, which to me makes it one of the most interesting. This work mentions cynocephali in considerable detail, the beginning of which is as follows.

John Mandeville: "Men and women of that isle have heads like dogs, and they are called Cynocephales. These people, despite their shape, are fully reasonable and intelligent."

In chapter 21 of this book, the author carries on to describe their culture, religion, weapons, clothing, and kingship. While this work is most likely the least credible, everyone agrees that the author wrote this book pulling from various legitimate sources. I, for one, chose not to ignore it especially given it agreed with every other source on the cynocephali that is known.

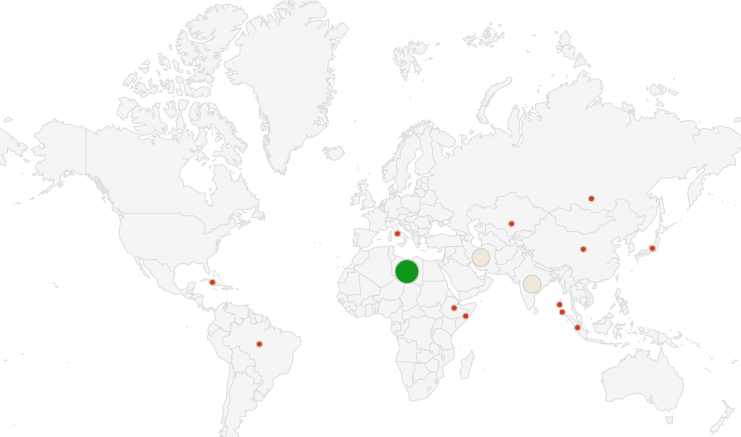

This list is far from exhaustive, and the written descriptions in some cases are actually quite extensive. Many men picked up their pens and chose to write about this strange and mystical race of creatures, oftentimes alongside very normal and verified historical accounts. With these men alone we have spanned almost 2,000 years from the 5th century BC through the 14th century AD, across multiple continents. This alone is quite a lot of information to wrap your head around. So in an attempt to visualize it, I plotted the locations where these and other written works say the cynocephali existed.

The more sources that speak of the cynocephali as being in that nation, the larger the dot becomes.

Upon constructing this chart, two things stood out to me.

- The majority of sources pointed to Libya (eastern Libya to be more specific), the runner-ups being Persia and India.

- The reach of the sightings of these creatures, according to historians and explorers, spans the globe.

This visualization helps, but still, three haunting questions lurk behind the dust upon these old and ancient books.

Were all of them wrong?

Were all of them lying?

Or were they telling the truth?

Unsure of the answers, I turned my head toward the first evidence I had found.

Cynocephali in Cartography

A standard method for cartographers to use when making maps is the use of drawings of animals that are relatively distinct to a location as the symbol of that area; Animals like elephants and oddly specific birds and unique cattle. Upon examining many maps of old one might find, as I did, that cynocephali appear on various maps as the unique creature of that region.

There are many ancient maps that are well-known for showing cynocephali, some more popular than others. These maps are all from different parts of the world and were created at very different times. This should give us pause.

Could this suggest that the belief in cynocephali was widespread in the ancient world and that many people saw these creatures as being real?

There are many maps we can turn to, but for the sake of time, let's look at just 4 of the most popular maps that include cynocephali.

The Piri Reis Map

The Piri Reis map is a world map compiled in 1513 by the Ottoman admiral and cartographer Piri Reis. Approximately one third of the map survives; it shows the western coasts of Europe and North Africa and the coast of Brazil with reasonable accuracy. Inscriptions in the margin detail how it was created from 20 to 34 existing source maps, both ancient and recent. Found in 1929, the remaining map fragment garnered international attention as its source map for the Caribbean is likely a map made by Christopher Columbus, otherwise lost.Wikipedia - Piri Reis map

This well-known, accurate, and legitimately utilized map shows cynocephali sitting and dancing in the South Americas.

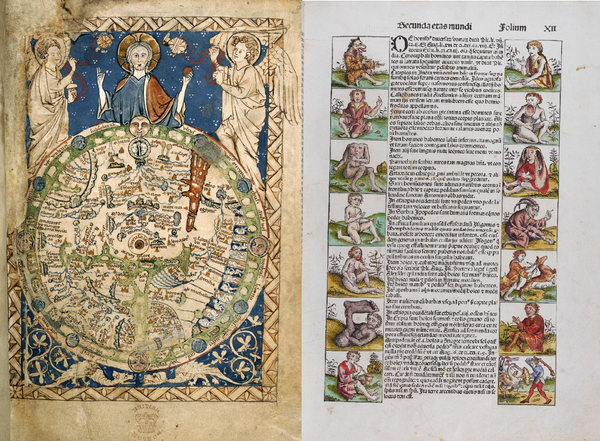

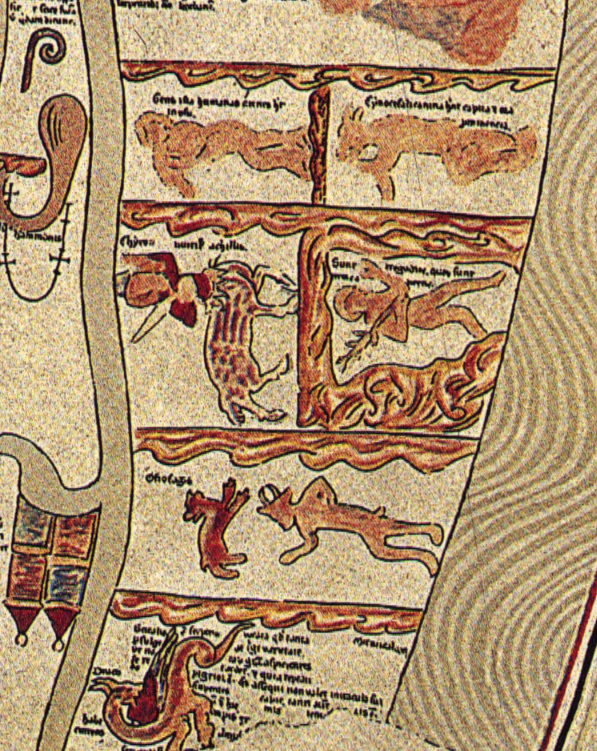

The Ebstorf Map

The map was found in a convent in Ebstorf, northern Germany, in 1843.[2] It was a very large map, painted on 30 goatskins sewn together and measuring around 3.6 by 3.6 metres (12 ft × 12 ft)—a greatly elaborated version of the common medieval tripartite map (T and O), centered on Jerusalem with east at the top.

Wikipedia - Ebstorf map

The Ebstorf map shows a cynocephaly next to a collection of other strange creatures, also commonly found on maps and in folklore.

We also see a more clear depiction, in the upper section of the map, of a cynocephaly holding a bow and arrow.

The Psalter Map

The Psalter World Map or the Map Psalter is a small mappa mundi from the 13th century, found in a psalter. No other records of psalters found from the middle ages have a mappa mundi.[1] The Psalter mappa mundi was likely used to provide context for the Bible's stories as well as a visual narrative of Christianity.Wikipedia - Psalter map

This map, much like the Ebstorf map, includes a section with a collection of creatures lined next to each other. This list includes cynocephali.

It is worth noting that some of these maps, like this one, are actually religious by design yet instead of focusing on angels and demons they include creatures that to us are strange and mythical.

The Hereford map

The Hereford Mappa Mundi is a medieval map of the known world (Latin: mappa mundi), of a form deriving from the T and O pattern, dating from c. 1300. Archeological scholars believe the map to have originated from eastern England in either Yorkshire or Lincolnshire before it was transported westward to the Hereford Cathedral in Herefordshire where it has remained ever since. It is displayed at Hereford Cathedral in Hereford, England. It is the largest medieval map still known to exist. A larger mappa mundi, the Ebstorf map, was destroyed by Allied bombing in 1943, though photographs of it survive.

Wikipedia - Hereford Mappa Mundi

Toward the top of the map, one can see a couple of cynocephali, partially faded but still clearly present.

So it seems that written accounts are not the only form of evidence. Ancient Historians and Cartographers alike described and depicted cynocephali as a very real part of the world that they lived in. These maps and writings, however, are far from the only evidence of this widespread understanding. Their depictions are found around the world in various forms in palaces, churches, temples, manuscripts, and more.

Cynocephali Depictions in Antiquity

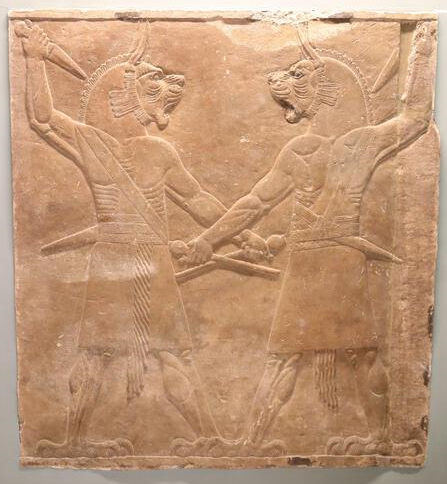

Besides the historical records and maps, it is important to mention that there is a plethora of ancient art pieces that showcase cynocephali beings. While wandering the massive halls of the British History Museum, we encounter one of the most famous examples of cynocephali. Turning the corner, imagination runs wild as our eyes fall upon a bas-relief from the palace of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh, which shows a group of cynocephali being brought before the Assyrian king.

.jpg/1200px-Exhibition_I_am_Ashurbanipal_king_of_the_world%2C_king_of_Assyria%2C_British_Museum_(45972455081).jpg)

These depictions create a sense of wonder, as one imagines the stories surrounding this work of art. This part of their history must have been important enough for it to be engraved in stone. What was the king thinking when he ordered it to be made? What were the thoughts and perspectives of the workers creating it? This piece displays them as mercenaries, warriors, or even assassins of a mystical kind. This is the darker side of cynocephali that history presents.

Vezelay - Basilique Sainte-Marie-Madeleine [1120 AD]

Leaving London, and journeying into Burgundy France we set our sights on the magnificent church of Vezelay.

Wandering its beautiful halls, we are met with the awe-inspiring depiction of Christ. With a second look, we look to the left of the top center and see a pair of cynocephali in clear detail.

How did cynocephali find their way into a religious place of worship? These constructions were incredibly expensive and designed with great care. What was so important about them that they were included in the design of this beautiful church?

Questions abound, but the answers won't be found here.

The Tombstone of Queen Fabia Stratonice

Churches were historically also homes to cemeteries, so perhaps after seeing cynocephali etched into a catholic church we shouldn't be surprised when we find that a cynocephalous is depicted on the tombstone of Queen Fabia Stratonice.

This depiction is most likely designed in reference to Anubis, the Egyptian guide of the dead. This would make sense both because of its clear Egyptian style as well as the fact that it is indeed a tombstone. All things considered, Anubis would be the obvious choice.

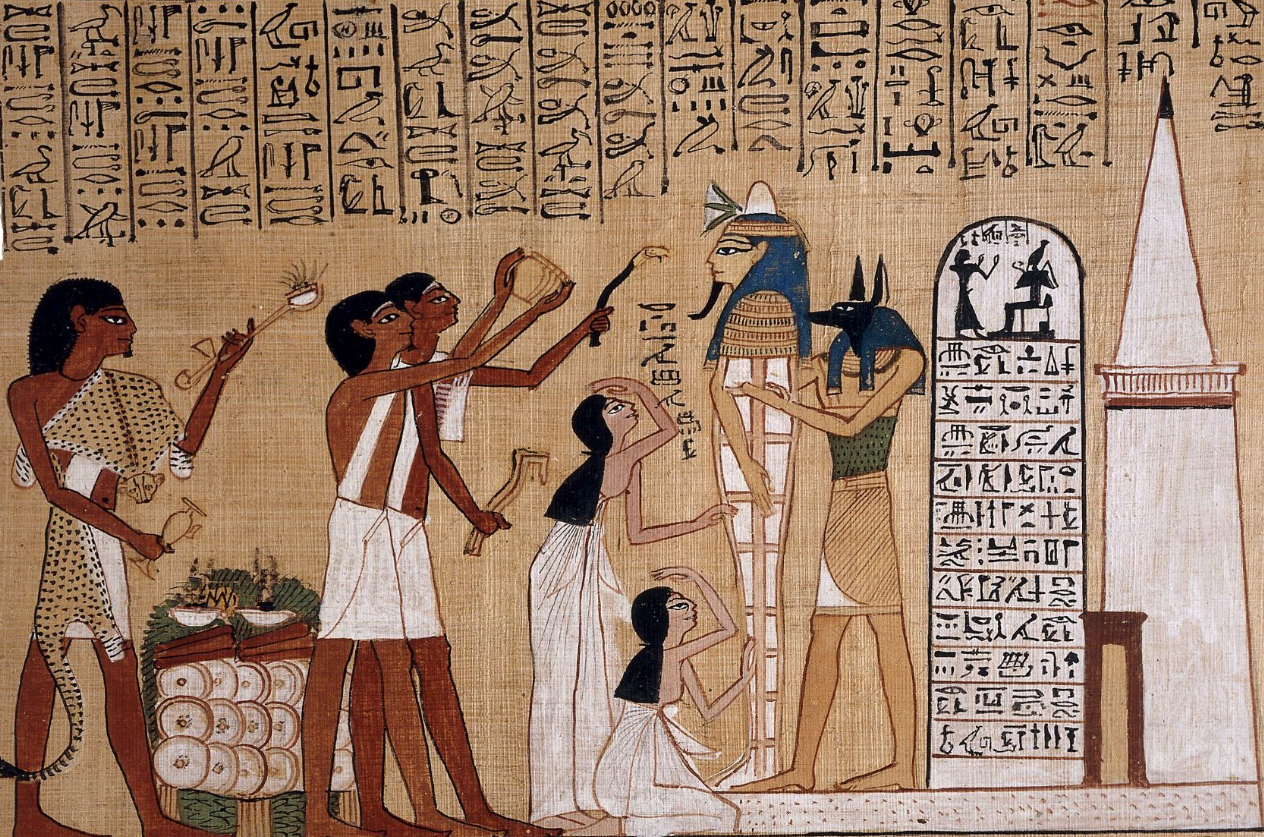

Book of the Dead [1275 BC]

Leaving Europe, hot on the trail, we journey into Egypt and stand in awe at the Egyptian Book of the Dead. Here we see Anubis standing tall as an iconic symbol of death and the afterlife. We've seen pictures of him before, but now we view him with fresh eyes... Wondering if there was more truth to his existence than we previously thought.

This ancient art, carved in stone and painted on walls, is just one of many. The world, it seems, is full of depictions of cynocephali.

Further journeys could take us throughout the rest of the globe.

- A terracotta figurine from China that dates back to the 2nd century BC shows a cynocephali wearing a Chinese-style hat.

- A mural from the Mayan city of Bonampak that dates back to the 7th century AD shows a cynocephali participating in a ritual. This suggests that cynocephali may have been an important part of Mayan culture.

- A rock painting from the Tassili n'Ajjer plateau in Algeria that dates back to the 9th millennium BC shows a cynocephali hunting a gazelle.

All of these displays are thought-provoking, but they aren't alone. There are more depictions that bear mention throughout the world. After appreciating the art of ancient days, we press on to examine further evidence of this fantastical race.

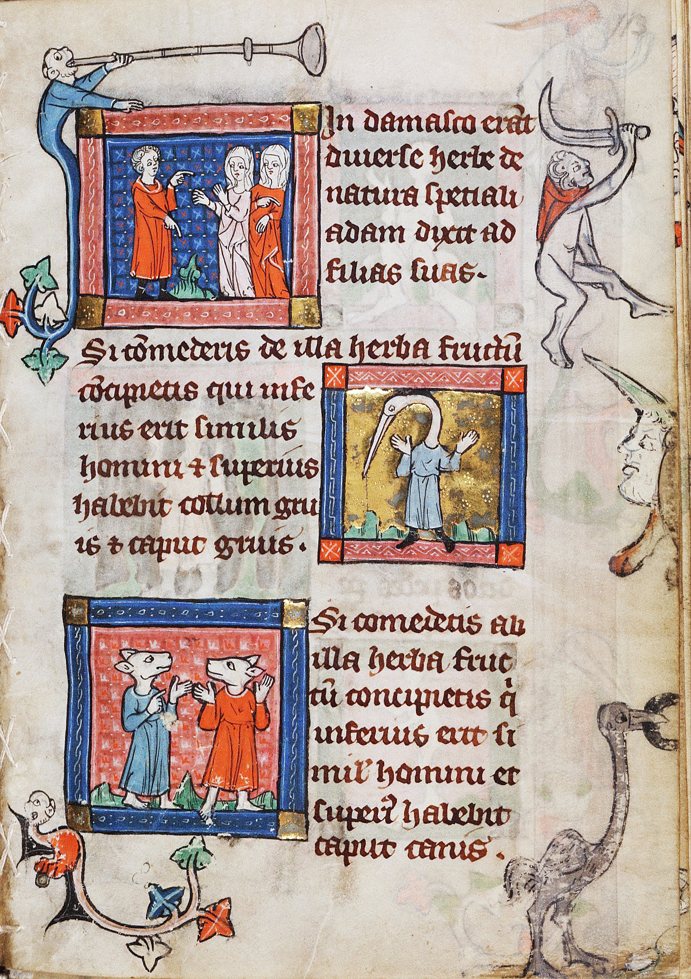

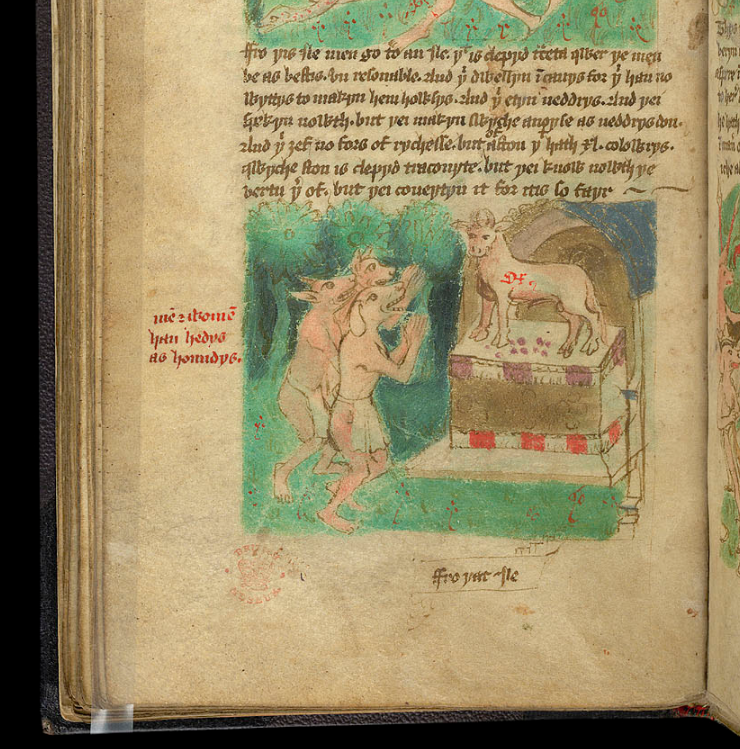

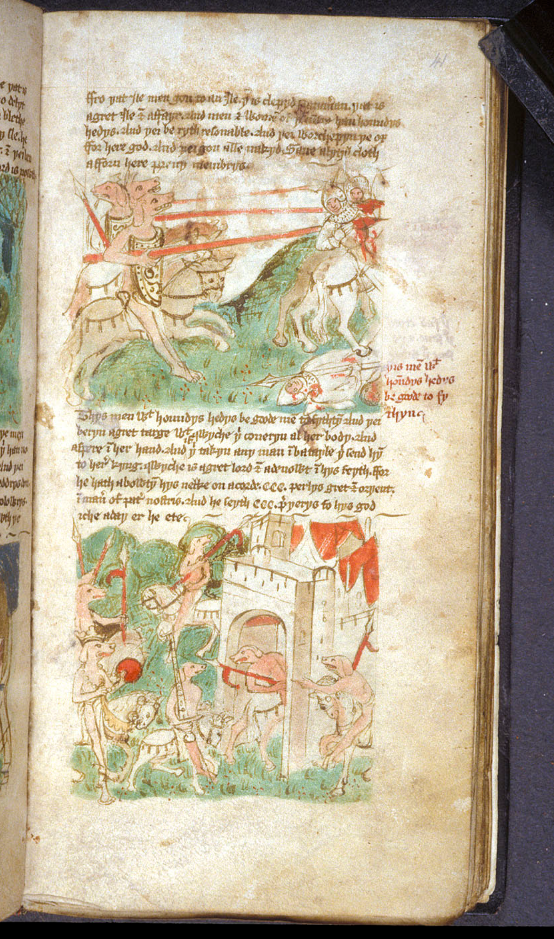

Books and Manuscripts

Many artistic depictions of cynocephali are found in books and manuscripts. Join me as I flip through the pages of written works from libraries around the world.

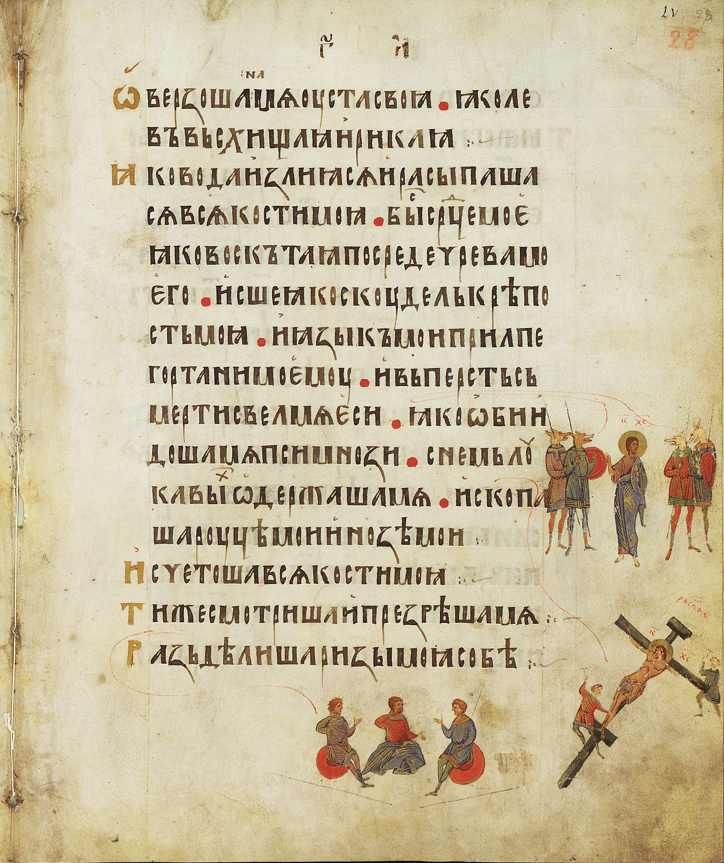

Kiev Psalter [14th century]

Here we find armed cynocephali depicted as peaceably speaking with Jesus Christ. Such a strange combination. Men with the heads of dogs, holding spears and shields, like we've seen before, but this time speaking with Jesus Christ. We've seen them in a catholic church, but this is still surprising. As strange as it is, it is not alone.

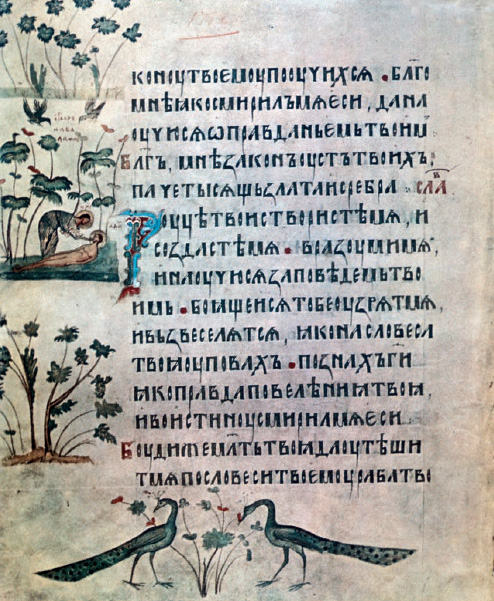

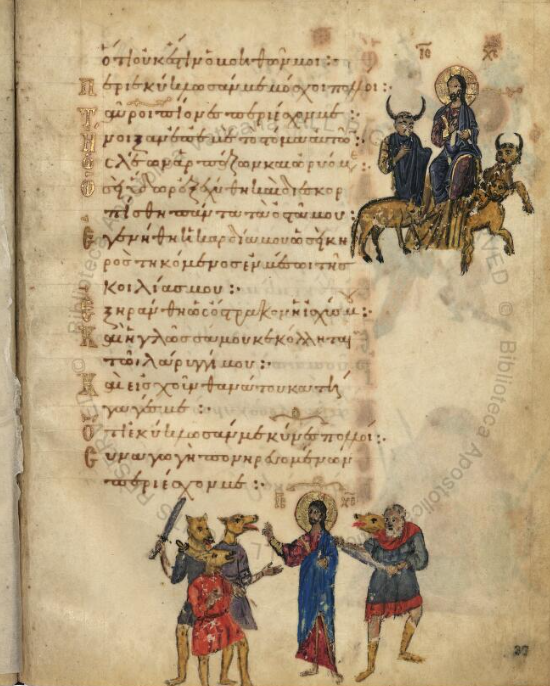

Barberini Psalter [11th century]

Here again, we see armed cynocephali speaking with Jesus Christ peaceably. But this too is not the only other work connecting them to Jesus Christ. What is this strange connection? We will explore this further, but for now let's remember that the early Catholic church wasn't the only producer of manuscripts with depictions of these creatures.

Rothschild canticles [14th century]

The Rothschild Canticles is a lavishly illuminated manuscript book of hours, compiled in Flanders between 1500 and 1520. It is named after the Rothschild family, who acquired it in the 19th century. It is notable for its rich illustrations, which include full-page miniatures, historiated initials, and marginal drawings using real gold and other precious pigments.

The Rothschild Canticles is said to be one of the most important illuminated manuscripts from the Northern Renaissance, partly due to its testament to the skill and artistry of the Flemish illuminators who created it.

The manuscript is currently housed in the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University.

In this work, we see cynocephali found among many other strange depictions. This is a spectacular example of the cynocephali as part of the collective consciousness of the Renaissance. For that to be true, though, there must be more. Let's take a look at another work from the 1500s.

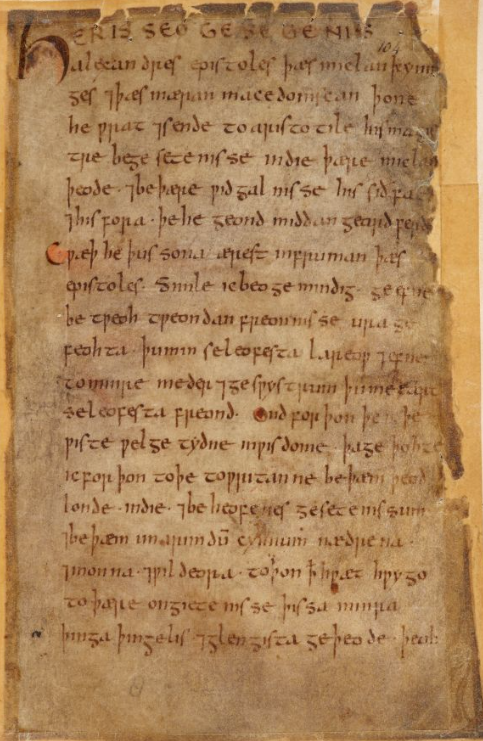

Travels by Sir John Mandeville [15th century]

Here we see the illustrations of the work by John Mandeville that we previously discovered. Seeing its painted drawings brings to life the many stories we've encountered and the whole picture slowly begins to form.

There are many, many, more manuscripts. The cynocephali are often depicted as trading, fighting, and in (catholic renderings) even being baptized or witnessed to Christ or saints. Much time can be spent simply searching, reading, and pondering these works but there is there more evidence to be found in, what seems to me, the least likely of places.

The Curious Case of Christopher

Saint Christopher has a very strange story about how he became a saint. It involves converting cynocephali that he encounters. We know now that the concept existed within the minds of some Catholics, but Christopher becomes a connection to a whole collection of evidence that no one would ever expect.

Passion of Saint Christopher, translated by William Henry Hulme (1889)

"I saw a race of men who had the heads of dogs, and their teeth were sharp like the teeth of lions. They were very strong and fierce, and they ate human flesh."

This quote is from the Passion of Saint Christopher, a text written after the close of the Renaissance that tells the story of the saint's life. In the story, Christopher encounters a group of dog-headed people while he is traveling through a forest. The cynocephali are initially hostile to him, but he eventually befriends them and helps them convert to Christianity.

The belief in cynocephali is a relatively common one in folklore across time, as we've seen. They are often depicted as being savage and cannibalistic, but they can also be portrayed as being wise and helpful. In the case of Saint Christopher, it is currently believed that the cynocephali represent the challenges and temptations he faced. By overcoming these challenges, Christopher was able to become a saint and a model of Christian virtue.

But were they nothing more than a metaphor? Or could this be part of a larger narrative that holds a grain of truth beneath the tales?

What is truly surprising is Christopher's reaction to these creatures as we see in his quotes about cynocephali in various works about his life:

The Golden Legend, translated by William Caxton (1483)

"The cynocephali were a fearsome sight, but I knew that I had to help them. They were lost and alone, and they needed my guidance."

The Life of Saint Christopher, translated by Henry James Coleridge (1847)

"I taught the cynocephali about the true meaning of Christianity. I showed them that there is more to life than violence and bloodshed."

The Lives of the Saints, compiled by Alban Butler (1756)

"The cynocephali were grateful for my help. They converted to Christianity and lived the rest of their lives in peace."

These quotes show that Saint Christopher had a compassionate and understanding attitude towards the cynocephali. He saw them as lost and misguided souls who needed his help. By teaching them about Catholic Christianity, Christopher claimed to have helped them to find a new path in life. At this point one wonders: If they symbolized his personal challenges, why would he have compassion toward them? What's more, if the story is true and he did encounter such beings and converted them to Christianity what does that mean for the Catholic Church?

Can such creatures be saved in a religious manner?

It turns out, this very question was a hot topic debated by Catholic theologians in days past. The Catholic Church debated whether cynocephali could be saved for quite some time.

Cynocephali and the Catholic Church

Sifting through the hundreds of letters, books, and manuscripts produced by the Catholic Church, one can find dozens of mentions of the cynocephali. Sentiment differs greatly as some viewed them as monstrous beasts and others as a malformed race of men who were still capable of salvation. This global conversation surprisingly lasted hundreds of years and involved abbots, bishops, and archbishops around and across Europe. The Council of Paris held in 859 AD, debated the possibility of cynocephali being saved religiously. The Council of Paris met for approximately two weeks, from November 25 to December 10. The purpose of the meeting was to address political instability, Viking invasions, and theological disputes. One of those theological disputes happened to be the possible salvation of the monstrous races, including the cynocephali. The Council concluded that cynocephali were not human, but that they were still capable of salvation if they were baptized.

For more information on the history of the Council, consider the following sources:

- The Council of Paris of 859 AD: A Reassessment by Janet L. Nelson

- The Acts of the Council of Paris of 859 AD edited by David H. Farmer

- The History of the Franks by Edward James

- Hincmar of Reims's Opusculum de Gratia Dei et Libero Arbitrio: This work includes a letter from Hincmar to Archbishop Erchanbald of Strasbourg in which Hincmar discusses the question of cynocephali salvation. In the letter, Hincmar argues that cynocephali are not human, but that they are still capable of salvation if they are baptized.

- Ansbald of Sens's Responsio ad Hincmarum de Remis de Causa Gotshalci: This work is a response by Ansbald of Sens to a letter from Hincmar of Reims in which Hincmar discusses the question of cynocephali salvation. In his response, Ansbald agrees with Hincmar's conclusion that cynocephali are not human, but he argues that they are still capable of salvation if they are baptized.

Though not a part of the Council, around the same time (9th century) Ratramnus of Corbie argued that the dog-headed people should be baptized to ensure salvation of their souls in a letter to Rimbert, the archbishop of Hamburg-Bremen (Epistola de Cynocephalis).

As previously mentioned, Augustine of Hippo writes on this topic in his book the City of God. He actually argues it shouldn't be absurd to us to think that such monstrous races might exist.

Augustine, City of God:"Accordingly, it ought not to seem absurd to us, that as in individual races there are monstrous births, so in the whole race there are monstrous races."

When it comes to the capacity for salvation, Augustine argued the following:

Augustine, City of God: "But whoever is anywhere born a man, that is, a rational, mortal animal, no matter what unusual appearance he presents in color, movement, sound, nor how peculiar he is in some power, part, or quality of his nature, no Christian can doubt that he springs from that one protoplast. The same account which is given of monstrous births in individual cases can be given of monstrous races."

Augustine's stance on the topic of the Cynocephali, and other monstrous races, is that their existence shouldn't be assumed to be either absurd or true, and if they do exist they should be treated as any other human with a deformity.

The debate over cynocephali and salvation eventually died down. However, it is still an interesting example of how the Catholic Church discussed the cynocephali and their salvation for hundreds of years.

Speaking of things that evolve over time, it's time our journey enters into the realm of folklore.

Folklore of the Cynocephali

To say that Cynocephali are found in folklore around the world in ancient times should be far from a surprise after the journey we've made throughout days of old. There are so many tales from ancient days that involve these creatures, whether in written mythologies or oral traditions, but after paying so much attention to the days of long ago I'd like to stroll through the halls of modern folklore involving this fascinating beast.

We've all heard of werewolves, the half-wolf half-human hybrids that fight vampires and strike fear into mankind. After what we've seen, could it be possible that this concept has roots in reality? Pausing to consider this, hundreds of examples can come to mind when thinking of werewolves. This concept is one that is mature and thoroughly developed. From movies to TV shows, to books, to stories told around campfires. Testimonials of people encountering these creatures still come out today. Could they still exist?

Dogman?

The modern folklore of dogman is a relatively recent phenomenon, with the first reported sightings dating back to the late 1980s. The creature is described as being a large, bipedal creature who is half man and half dog. It is said to be covered in fur and to have a long, bushy tail. Dogman is often said to be aggressive and dangerous, and there have been a number of reported attacks on humans.

The modern folklore of dogman is thought to have originated in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, where there have been a number of reported sightings. The creature has also been reported in other parts of the United States, including Wisconsin, Illinois, and Ohio. There have also been reports of dogman sightings in Canada and Europe.

The modern folklore of dogman is often attributed to the popularity of cryptozoology, the study of animals whose existence has not been verified by science. Cryptozoologists believe that dogman is a real creature, and they have collected a number of eyewitness accounts and physical evidence, such as footprints and hair samples. However, the scientific community has largely dismissed the existence of dogman, and there is no definitive proof that the creature exists.

Despite the stance of government and industry-financed scientists, the modern folklore of dogman continues to be popular. There are a number of websites and forums dedicated to the creature, and there have been several books and documentaries published about it. The creature has also been featured in a number of fictional works, such as novels, movies, and video games as well.

Could this have been staring us in our faces this whole time? Could this strange concept be a reality, and one so close to home?

Summary and Supposed Origins

Is dogman, are modern cynocephali in general, real? Are there half-human half-dog creatures walking around in the dark? If there are I wouldn't be shocked. Given just how many people, places, and things across time and around the globe point to the existence of cynocephali it's hard to deny their existence. Why so many respected historians? Why so many maps? Why is it that the Catholic church, instead of debating IF they existed, debated if they could be saved by Jesus? Why are there so many carvings, drawings, and paintings (all of which were expensive and time-consuming to create)?

If they did (and or do exist), where did these creatures come from? Perhaps both mythologies and the Bible have contained the answer this entire time. Perhaps they are descendents of hybrid creatures of Genesis 6. What if they are the result of fallen divine commingling with beasts and humanity, as many ancient texts describe? A descendent race of one of the 3 races we read of in antiquity.

For more on this concept of cryptid creatures in the Bible stemming from Nephilim listen to the following podcast episodes on All Out War and Confessionals where I discuss the basics and cite primary sources:

The concept of strange part-human part-animal beings is shared across nearly all cultures including the ancient Jews. Could there be truth to it? The Bible itself mentions Satyrs (among other creatures), as do Jewish history books and even the Talmud (their books of rabbinic laws). These races are described by various sources as either a product of or are the descendants of the Nephilim and their ancestors. Whatever the case, civilizations have seemingly left evidence for the existence of cynocephali across the globe and throughout time. Regardless of everything else, that should be addressed.

What are we to do with this?

Dissmiss it? Or investigate?

Works Cited

- Herodotus. The Histories. Translated by A. D. Godley. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1920.

- Pliny the Elder. Natural History. Translated by H. Rackham. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1942.

- Marco Polo. The Travels of Marco Polo. Translated by Ronald Latham. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin Books, 1958.

- Mandeville, John. The Travels of Sir John Mandeville. Translated by C. W. R. D. Moseley. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin Books, 1983.

- Ctesias, Indica Fragment (summary from Photius, Myriobiblon 72) (trans. Freese) (Greek historian C4th B.C.)

- Megasthenes. Indica. Translated by J. W. McCrindle. The Indian Texts Series. London: Trubner & Co., 1877.

- Aelian. On Animals. Translated by A. F. Scholfield. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1958.

- Solinus. Collectanea Rerum Memorabilium. Translated by J. C. Rolfe. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1935.

- Augustine. City of God and Christian Doctrine. Edited by Philip Schaff, D.D., LL.D.

- Isidore of Seville. Etymologiae. Translated by Stephen A. Barney. The Catholic University of America Press. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1982.

- Manetho. Aegyptiaca. Translated by W. G. Waddell. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1940.

- Berosus. Babyloniaca. Translated by E. Theodosius. Fragmenta Historicorum Graecorum, Vol. 1. Edited by C. Müller. Paris: Didot, 1841.

- Pomponius Mela. De Chorographia. Translated by F. E. Romer. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1954

- Arrian. History of Alexander the Great. Book VI, Chapter 29. Translated by Aubrey de Selincourt. Penguin Classics, 1958.

- Vincent of Beauvais, Speculum Naturale, 36.68

- Ottewill-Soulsby, S. (2021). City of Dog. Journal of Urban History, 47(5), 1130-1148. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144220910139

- Ratrumnus. Espistola De Cynocephalis. Carolingian Civilization: A Reader, Edited by Paul Edward Dutton, pp. 452-455.